It’s that time of year again - we’re shopping for school supplies, teachers are returning to their classrooms, and students (as well as their parents) are eagerly awaiting the news as to who their teachers will be. As a parent of two school-aged boys, it’s also the time of year our family starts making predictions about the year ahead. “I think Miles will do so much better in reading this year.” “Taylor is probably going to get in trouble a lot, but maybe he’ll also test into the gifted program.”

It’s an innocent practice in anticipating the successes and struggles we’ll experience in the year ahead, but without knowing it, we’re also shaping how we will perceive these experiences as the year unfolds.

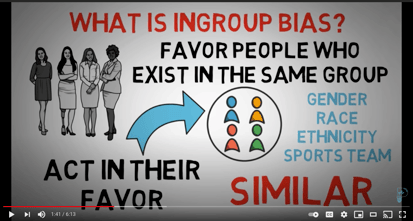

We’re creating a bias -- or a lens through which we look at factual information that is based on an assumption, opinion, feeling, trend, inclination, or tendency -- that impacts how we view those facts. Biases can come from individuals (like when a parent believes that her child is the best athlete on the basketball team) or collectively among a group (like how fans of any other NFL team feel about the Dallas Cowboys).

In schools, individual and collective bias can have a significant impact on how teachers and leaders use data to make decisions. Whether they are reviewing student assessment data or reading feedback from parents in a recent survey, their assumptions and opinions are impacting the conclusions made about what they see in the data. It’s a human and natural part of processing information - there’s nothing inherently wrong with it - but it does matter. And it is important that we acknowledge how these biases impact what we see.

At Education Elements, we’re working with schools and districts to help them build stronger data culture. We believe that a strong data culture is, among other things, one that PROMOTES EQUITY AND INCLUSION, meaning that there’s an intentional effort to:

- Collect data that are representative of all stakeholders

- Use data to shine a light on systemic inequity or injustice

- Name and neutralize individual and collective biases when using data

To better understand that last point - how to name and neutralize bias when using data - I sought the guidance of one of our newest tEEm members Jake Rowley. Jake is a Senior Research Scientist with deep experience in helping districts and schools gather, organize, and report on student, teacher, and family perspectives using Tripod Education’s nationally normed, validated, and recognized surveys. Jake shared the following recommendations for how to neutralize bias when using data.

Know how your bias shows up. Jake explained that in his experience, individual and collective bias will lead to teachers and leaders dismissing critical feedback. Tripod’s 7Cs survey asks students to provide actionable feedback on instructional practices that are widely supported by research to predict higher student achievement, engagement and motivation, as well as success skills and mindsets. But when school leaders in particular are so used to being cheerleaders and advocates for their staff, they focus on the positive and what is going well. More specifically, leaders may have a strongly held belief that instructional quality is high throughout the school. This view can trickle down to teachers, and can lead teachers to discount negative feedback from students by attacking the ability of students to be credible evaluators of the classroom learning environment.

Name your knowns and unknowns. Jake shared that he often describes surveying as similar to checking the oil in your car. You may have an idea of what you’re going to find when you check, but you don’t know for sure if you need an oil change until you look at the results. Similarly, a school team may have some strongly held beliefs about what they are expecting to see in their data before they review the results. By recording these assumptions prior to collecting data (for example, by having team members do their best to take a survey from the perspective of the group they are surveying), the team can compare their preconceptions against the data, and identify gaps - both positive and negative - between their assumptions and what they see in the results. Similar to an oil change, this kind of careful review of the findings followed by acknowledging growth areas and action-oriented goal-setting, can be indispensable in supporting successful performance for the long-term.

Look for stories in the data, both expected and unexpected. Jake explained that when reviewing survey results, a team will often come into the conversation looking for specific storylines. For example, they may want to compare responses from black female students to white female students, or between elementary students and middle school students. Comparing data sets is a helpful exercise in testing assumptions about the status quo, but, according to Jake, if the analysis stops there they run the risk of overlooking glaring disparities in lived experience for other subgroups (for example, between transgender and cisgender students).

Research has shown that most adults have bias blind spots, meaning that they are far less likely to detect bias in themselves than others. In order for teams to understand how biases impact what they see in their data, and to avoid the mistakes that Jake described above, we recommend starting data conversations with each person by naming a bias that they bring into the conversation even before they look at the data.

For example, before reviewing student data from a midyear interim assessment, teachers may name biases including:

- “I think my students will score the lowest on this skill, and the highest on this skill.”

- “I’m expecting to see that Student X really struggled with this.”

- “There were a lot of distractions the day our students took this test. I bet the scores are low.”

We should discuss how these assumptions, opinions, tendencies, etc. might impact what the team sees in the data, and keep these top of mind as we review the facts.

For my husband and me - as our kids start this new school year - it means naming where our bias shows up, being specific about what we know and don’t know about their experiences, and being open to storylines we’re not expecting. Our hope is that this will make us more aware and more understanding of what they need from us this school year, and help us to make better informed choices about how we can support them.

Here’s to parents, students, and teachers everywhere; may we all experience a wonderful beginning to this new school year.

More Data Culture reading

Blog: A Four Step Process for Developing Data Culture in School Districts

.png)