For more than a century, standardized testing results have been used to measure the success of students, teachers, and schools – and even to mark our global competitiveness or lack thereof. These data have driven significant education policy and funding models at the national and state levels, and school districts devote anywhere from one week to one month each school year to student assessments alone, costing an estimated $1.7 billion each year.

But simply having data is not enough. Today, many school districts struggle with DRIP syndrome: they are Data Rich and Information Poor, because their ability to organize, process, and understand school data is limited. They may have deeply embedded practices where data are used only superficially to check a box. Data use may be inconsistent across the organization or only occurs in silos. Some school districts may even have beliefs and norms – a culture – that actually diminish the potential benefits of assessment and data collection. The truth is that the work to dismantle bad habits and unhealthy systems is really, really hard. But if we are going to rise to the challenge of truly closing achievement gaps, especially those exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, our schools need better data and a stronger data culture. We need to enable them to make more informed and more equitable decisions about how to improve educational experiences and outcomes for all students.

For decades we have based many of our policy and practice decisions on standardized testing data. These tests are, and were, incredibly high-stakes for students, teachers, and schools. The stakes were intended to hold us accountable for educating all children. But the impact of decisions based on these tests is debatable at best. We know that standardized testing data, when viewed in isolation, represent a limited view of student success and can even mislead us. We know the policies we’ve enforced and the decisions we’ve made based on these data have failed to close persistent achievement disparities across income levels and between white students and students of color, even after more than 50 years of testing.

And now, we are desperately seeking to understand how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted students. For some, the pandemic has and will continue to exacerbate these achievement gaps. Other students, who have traditionally struggled in our school systems, have found ways to thrive in remote learning. School districts now face the enormous challenge of understanding how this global pandemic has impacted their most vulnerable students, and we cannot rely on the same information and the same systems that have failed us for decades to guide us through this challenge.

Report: Strength in Numbers: State Spending on K12 Assessment Systems - Brookings

Article: 6 Common Mistakes to Avoid for a Stronger Data Culture

Research: Listen to Us: Teacher Views and Voices - Center on Education Policy

The education industry has experienced a surge in innovation, and in fact, spending specifically in EdTech is expected to nearly double just in the next five years. But most of the advancements specific to education data have been focused on producing more and better data or building technical systems (such as platforms and dashboards) for displaying data. Without equal investment in data culture, or the human factors related to understanding and using data, the efforts tied to data quality, infrastructure, and technology will fail to have an impact.

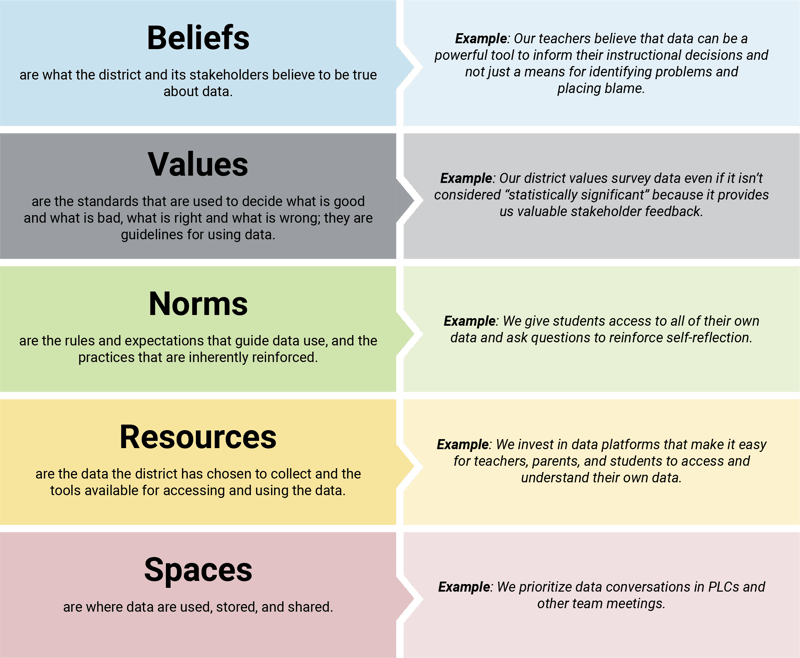

A school district’s data culture can be defined by beliefs, values, norms, resources, and spaces.

Today, many school districts struggle with DRIP syndrome: they are Data Rich and Information Poor because their ability to organize, process, and understand data is limited. With our new guide, we provide strategies for district and school leaders to better understand their existing data culture and identify the ways in which it needs to be improved.

Today, many school districts struggle with DRIP syndrome: they are Data Rich and Information Poor because their ability to organize, process, and understand data is limited. With our new guide, we provide strategies for district and school leaders to better understand their existing data culture and identify the ways in which it needs to be improved.

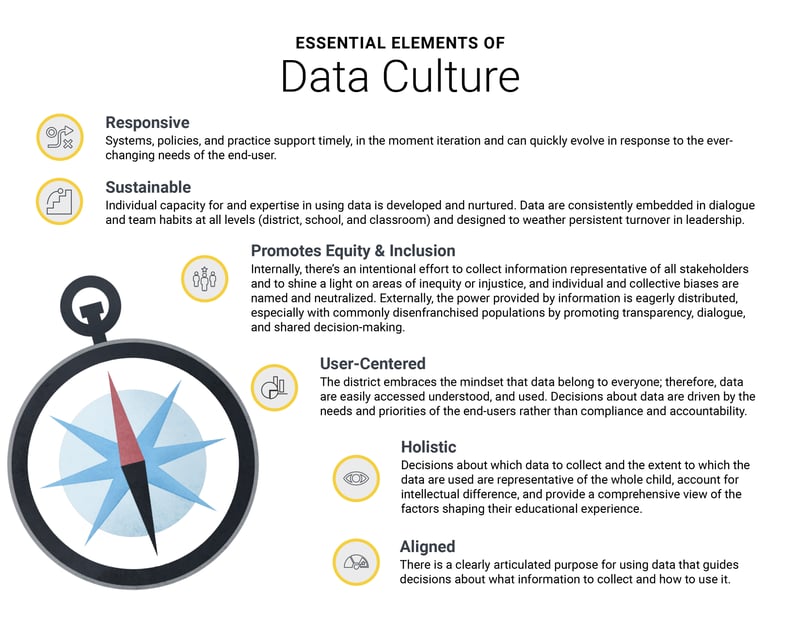

In order to develop a strong data culture, one in which the human factors are prioritized, schools should work toward the following:

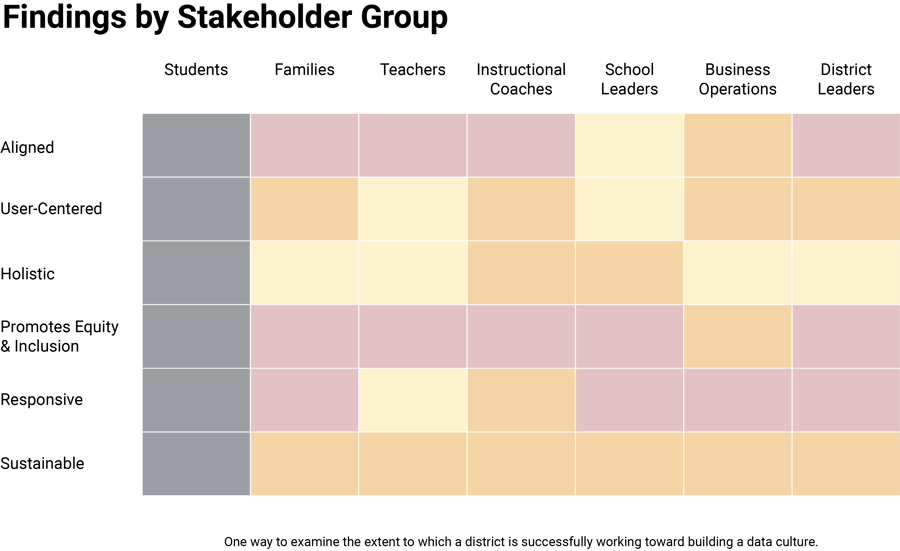

We believe that districts can work toward building a strong data culture – one that is democratized and useful – by examining and strengthening their practice in six areas. These Six Essential Elements of Strong Data Culture provide a framework for district and school leaders to better understand their existing data culture and identify the ways in which it needs to be improved.

The Education Elements team shares our essential elements of data culture in schools and dives into why you need to change the way you think about data (including how to map your data decisions in schools and classrooms). You might already collect a lot of information in your district, such as traditional attendance data, platform engagement information, student access to at-home computers/internet, and data usage for education tech platforms. Some of this data we know already exists but we’re not quite sure yet how to use it. And in some instances, we might not collect enough data but we need to use the information frequently.

There is often a misperception that only certain people belong in data circles or on data teams – technical experts, academics, and researchers, for example. This often due to the following.

In order to have a strong data culture, however, school districts must make intentional efforts to demystify and democratize data for all of their stakeholders. They must embrace the mindset that data should belong to everyone and ensure that data are easily accessed, understood, and used by all kinds of stakeholders.

In this webinar short, the Education Elements team talks about specific ways you can incorporate data culture to improve decision-making for staff and students this school year. We give a few examples of who could benefit from more easily accessible data and how they can utilize it. For a more comprehensive overview of data culture and tips for practical ways you can start applying this knowledge, check out the full webinar linked below!

Examples of this include cases like the following:

A more inclusive data culture requires a mindset shift from “we collect data so that we can do something for” people, to “we collect data so that we can do something with” people. The shift from a “for” to “with” mindset is subtle but it leads to more inclusivity, makes space for agency, and creates buy-in and motivation that can lead to better results.

When a school district has a “with” culture that promotes equity and inclusion, it means that internally, there’s an intentional effort to:

Externally, the power provided by information is distributed, especially with commonly disenfranchised populations by promoting transparency, dialogue, and shared decision-making.

School districts with a data culture that promote equity and inclusion believe that:

School districts with a data culture that promote equity and inclusion do the following:

At Education Elements we believe deeply in the power of helping school districts become more responsive organizations. We believe that schools that are responsive to the changing conditions around them can better respond to the educational needs of their students. But in many school districts, this means moving away from deeply entrenched school management and leadership practices that were developed for educational success in the early 20th century – practices that were designed for a much less diverse student population and to prepare students for highly structured environments, like factories and large organizations.

In order to stay competitive and seize the opportunities presented by new ideas and innovations, school districts must reinvent how they work and embrace organizational models that allow for continuous innovation, learning, and change. This means more distributed authority, getting comfortable with experimentation and “safe enough to try”, planning for change instead of perfection, sharing information more openly, and focusing on being learning organizations.

A strong data culture can drive responsive practices within schools and teams, and across districts as a whole. In districts with strong data culture, systems, policies, and practices support timely, in the moment iteration. When the needs of their end users change, a responsive data culture can quickly pivot to support those needs. For example, when a global pandemic shuts down schools indefinitely, district and school leaders can immediately access information they’ve always collected but rarely used, like which students have access to computers at home.

In a responsive data culture, various data are collected for evaluative purposes, to determine whether or not a program or intervention achieved its intended outcomes. But data are also collected for responsive improvements and iterations along the way. For example, when a school implements a new math curriculum, the principal doesn’t wait until the end of the year to look at the data. She reviews data every month, or even every week to determine whether the program is being implemented with fidelity and whether or not there are signs of incremental change. Teams establish habits of using and talking about data and the learning from those conversations allows them to be agile in times of rapid change.

The reality is that we don’t know yet how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted our students, or how the crisis may have impacted pre-existing conditions. And worse, as veteran Boston Public Schools teacher, Neema Avashia, describes in EdWeek, “The people in charge of making policy decisions are so far removed from the experience of pandemic schooling that their decisions don’t even seem to reflect the lived realities of young people.”

School districts with a strong data culture take a holistic approach to data-based decision making by broadening the scope of what they are investigating. Rather than narrowly focusing on “learning loss” as evaluated by standardized assessments, they ask students directly about the impact of the pandemic on their relationships, their mental health and wellness, and how remote learning has improved or worsened their educational experience. They leverage empathy interviews, focus groups, and forums to collect qualitative data, and their quantitative data will be more representative of the whole child.

As ASCD describes, this means going beyond the narrowly defined academic success measured by high-stakes tests to one that focuses on the long-term development and success of all children. In a holistic data culture, data are collected and analyzed in order to also understand the extent to which:

Districts with a strong data culture are also able to be more responsive to the quickly changing needs of students and teachers. In post-pandemic schooling, this will likely mean helping both students and teachers take a more mastery-based approach that prioritizes the skills and competencies students most need in order to be successful at the next stage of school and life. A responsive data culture can quickly pivot to provide the critical information students, teachers, and school leaders will need to build schedules, structures, and curriculum units that support deeper learning, rather than superficial coverage.

Blog: What Responsive Planning Looks Like in a Strong Data Culture

Article: Students Respond to Adults’ Fixation on ‘Learning Loss'

Article: Whole Child

Article: Using Data in Schools to Learn Fast

As districts set out to establish and nurture a stronger data culture, they should consider the following steps.

Through it all, school districts (with the help of state agencies and nonprofits) have come a long way in the areas of infrastructure and interoperability. Far less attention and effort has been focused on building data culture in schools. And without data culture, all of these efforts, including those tied to data quality, infrastructure, and technology, will fall flat and fail to have any lasting, equitable impact. That's one reason why we continue to be encouraged by those districts willing to reflect on these recommendations and invest in building their data culture.

Survey: Self-Assessment on Building a Strong Data Culture

Blog: Four-Step Process for Developing Data Culture

Guide: Strategic Prioritization Guide

Article: Strategic Prioritization Using Even Over Statements

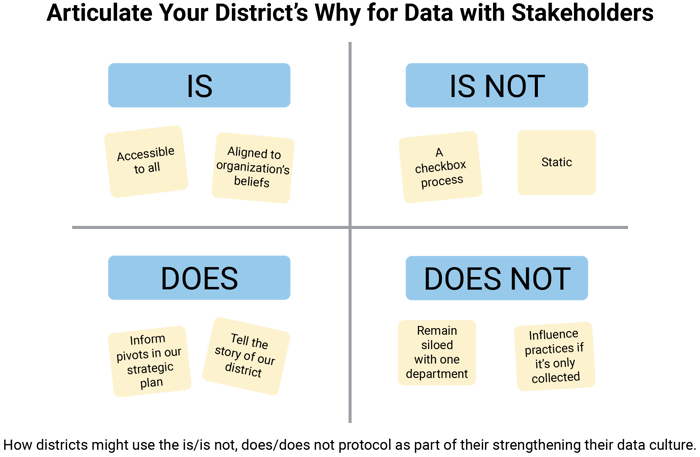

Article: Activities for Making Agile Retrospectives More Engaging: Is-Is Not; Does-Does Not

Article: Activities for Making Agile Retrospectives More Engaging: Problems and Actions

Worksheet: Prioritization Exercise