The end of average is here. Or at least, you'll probably think it's close once you read Todd Rose's The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World that Values Sameness.

Rose gave the main keynote at last year's iNACOL conference. Drawing on material from his new book, Rose offered three compelling changes to how we consider individuality (or anti-average thinking) to better solve social and self-problems.

My colleagues who attended iNACOL thought Rose's ideas demonstrated why personalized learning is so essential, both for our schools and for how we approach learning in general, and came back talking about him. Unable to attend iNACOL, I resolved to read The End of Average myself.

After reading it, I can affirm that Rose does a great job of unpacking our ingrained addiction to comparing our lives and actions to average. As a test of my own understanding, I wanted to connect each of his "principles of individuality" to tangible changes that a school district might consider to better personalize learning.

- 1. The Jaggedness Principle

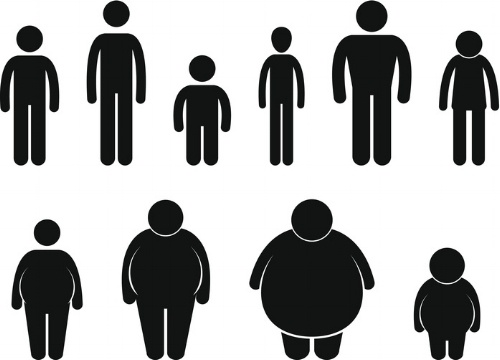

According to Rose, jaggedness is the idea that "we cannot apply one-dimensional thinking to understand something that is complex and jagged." In this situation, Rose defines "jagged" as the characteristic of having many weakly-related dimensions.

He illustrates this characteristic using the contrast of height versus human size. Height is one-dimensional: you have one height, and you can be measured objectively against others' heights. Size, on the other hand, is comprised of many characteristics, such as weight, height, width, length of limbs, among others. Human size is jagged.

In a conventional classroom, we might see a lot of non-jagged thinking. Simply walk into an average middle school: you'll see kids of all shapes and sizes, yet I bet nearly all student desks look the same.

More innovative schools are already work to accommodate jaggedness through flexible classroom seating and alternative furniture, meeting the varying physical needs of students. Some kids may sit on bean bags, others at desks, some on the floor. When Education Elements hosts a Design Academy with a new school partner, one of our first activities is reimagining and redesigning the classroom space.

Beyond physical space, you might see schools implementing co-teaching models, acknowledging the jaggedness of teachers' instructional skills. It's likely that two equally-great teachers could have teaching strengths that dramatically differ. By co-teaching, these teachers can divide up responsibilities according to their specialities, to make work more enjoyable and benefit students. In the Enlarged City School District of Middletown, even elementary school teachers develop instructional specialities, collaborating with their peers to deliver more impactful learning experiences to students.

Finally, just as there is jaggedness to what makes an ideal instructional environment, there is jaggedness to what learning looks like. Howard Gardner's introduced this very idea in his seminal 1983 book about multiple intelligences, proposing that there are multiple ways to "be smart", making intelligence and thus learning a jagged process.

- 2. If-Then: The Context Principle

I found this section to be most profound for my own thinking. I grew up thinking in fixed mindset statements such as, "Oh, Johnny is smart," or "Susie is mean."

Instead, Rose proposes that we think of personality traits and skills through a lens of conditional if-then statements. For example, if Johnny is in math class, then he is smart. Or, if Susie is feeling bullied, then she is mean. If applied to learning habits, this could sound like, "if I'm in quiet space, then I write better."

Rose argues that looking at personality or abilities in context "allows us to deal more productively whenever we see our child, employee, student, or client engaging in negative behaviors that we want to change." He continues. "Instead of asking why they are behaving in that way, we can reframe the questions in terms of context and ask ourselves, 'Why are they behaving that way in that context?'"

This concept has a direct application to how teachers address behavioral issues in a class, and in many ways, teachers have been doing this forever. A teacher would know that when Susie is put next to Chelsea, she becomes feisty. Separate the two of them, and Susie becomes an angel again.

Yet applied more generally to personalized learning, an if-then lens becomes a powerful tool to help teachers differentiate instruction. For example, if a teacher has a three-station rotation model set-up in her classroom, reflecting on how specific students perform in each station — rather than evaluating student performance on average across all stations — could allow the teacher to more effectively group students.

A teacher could also leverage this perspective to promote student reflection and ownership of learning, a key component of the Core Four of Personalized Learning. In this Edutopia article, a middle school student reflects and shares how he actually prefers a table to a classroom couch, stating "when I get down into a couch and am more comfortable, it's almost like it's a bit distracting. It's not exactly the environment I want to be working in, but for the other people, clearly they have their optimum working environments." By asking students to think about how they learn and behave in different environments, a teacher might help students be more intentional in choosing a particular classroom station, asking questions, or collaborating with peers. When students better understand how their learning habits change in different environments, and they're given choices, they're empowered to positively affect their learning experience.

- 3. Pathways

When I hear pathways, I think of the academy program that my public high school implemented when I was a freshman. Each student could select one of four different career-related set of courses (academies) that fit their interest. I was in the Business academy at first, eventually switching to Fine and Performing Arts.

What Rose advocates for is similar, but more nuanced. He states that there is no singular, right path for any human process. As an anecdote, he shares the discoveries of researcher Karen Adolph that there are at least twenty-five pathways that infants can take to walking, not one typical progression. In Adolph's research, some infants skipped developmental stages like crawling that were previously thought necessary in any healthy child's path to walking. In this, Rose argues that there is no right way to do something; there are many pathways to success.

Some schools are moving away from "one-path-for-all" thinking. One tactic to support different learning paths in the classroom is to allow students to demonstrate mastery of knowledge in different ways. Rather than requiring all students to take a test to show they understand a concept, teachers could allow students to choose between a project, an essay, or test. This freedom promotes students demonstrating knowledge through the path that best fits their own preferences.

Another way schools are supporting multiple learning pathways is through Competency-Based Education. Competency-based education, or CBE, is the idea that advancement through a system of learning is based on mastery, not seat time. Under a CBE model, teachers seek to facilitate students learning at their own pace. If a student is able to master concepts more quickly than peers, she should be able to move ahead onto new lessons. The idea of CBE, if radically scaled across grades, could results in students advancing through different grade levels of subject matter at different paces.

CBE is still a struggle for most districts. Its basic tenets can be challenging for a system that has been historically defined by seat time and grade levels. But slowly, districts are taking brave steps to test it out.

Education Elements' Mike Wolking and Amy Jenkins lead a workgroup for the League of Innovative Schools where superintendents from around the country are collaborating to understand how CBE can afford students a more personalized and impactful learning experience. Wolking and Jenkins have even developed a CBE framework for districts to consider when considering how to support a variety of learning pathways and proficiency levels.

Through jaggedness, the if-then principle, and pathways, Rose argues that we can move beyond the "averagarian" thinking of the industrial age to address some glaring societal challenges. His book The End of Average is a powerful contribution to the growing cry the against "one-size-fits-all" and "one-path-for-all" thinking to which many attribute our current education dilemmas. For transformations like personalized learning to be successful, education leaders should consider integrating Rose's paradigms not only into classroom instruction, but into the work practices and culture of the entire district.