Over the last 10 years, we have seen a shift in how states, districts, schools, and teachers access and leverage high-quality instructional materials to guide instruction. With so many options, deciding what’s most appropriate for your individual students and community can seem overwhelming. We also know that the current challenges districts are facing – including how best to address the immediacy of schooling loss – means that the stakes around curriculum and academic decisions are higher than ever.

Teachers and school leaders know that materials matter, but don’t always have access to the high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) their students deserve. Additionally, we know that instructional materials are not the only element necessary for changing teacher practice or improving student outcomes. The following guide shares key practices and outcomes for establishing a shared instructional vision, selecting HQIM, prioritizing professional learning for educators, and ensuring that these improvements stick by fostering collaboration, internalization, and practice.

Teachers spend 7-12 hours per week searching for and creating instructional resources, many of them unvetted. When teachers don’t have access to strong materials, they search for them online, often leading to inconsistent quality and weak alignment to the standards.

HQIMs are cited as a top funding priority for teachers, but access to high-quality materials is disproportionate, with low-income students less likely than high-income students to have quality content and curriculum in the classroom. Providing equitable access to HQIM is critically important as we address schooling-loss across the country. According to The Opportunity Myth, a report released by TNTP in 2018, “When students who started the year behind had greater access to grade-appropriate assignments, they closed the outcomes gap with their peers by more than seven months.”

And, when we use HQIM, we are more likely to engage students. Another study similarly illustrated that teachers – using aligned materials – engaged students in mathematical practices at a significantly higher rate than teachers who did not have access to aligned curriculum. The bottom line? Materials matter. They are the core element of effective and equitable instruction and improved student learning. But are they enough?

Blog: Solving Curricular Challenges: Driving Change through a Clear Vision

Blog: Strange Bedfellows: The Marriage of Personalized Learning and High-Quality Curriculum

We believe that HQIM are a necessary foundation for strong instruction, but on their own they are not sufficient for changing teacher practice or leading to improved student outcomes.

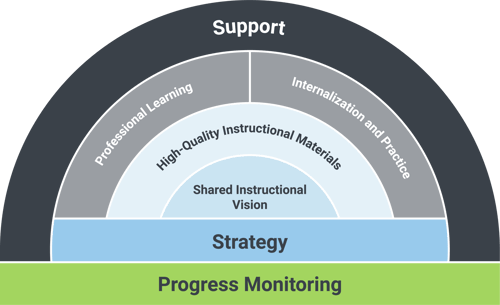

Our framework to support the successful implementation of HQIM requires a comprehensive strategy of aligned support that takes into consideration teacher and leader capacity and investment, professional learning, and opportunities for lesson internalization, planning, and practice.

Selecting and implementing HQIM begins with a shared understanding of what strong instructional practices and materials look like and aligning that vision at the classroom, school, and district levels.

What does this look like in practice?

What are key outcomes of a shared instructional vision?

Though it has taken years, the current market for HQIM is strong; and now it presents states, districts, and educators with a different set of challenges: so many options. How do you select the best materials to meet your needs and context, and how do you leverage these materials to foster student-centered learning?

If we know what our students need, as well as the strengths and limitations of our current materials, then we can create a prioritized plan for all stakeholders to use to move forward. Conducting an initial review of existing materials will help you determine the alignment of your materials to student needs and the district's vision for strong instruction. Four key domains to consider include:

In addition to these four domains, additional domains can and should be considered based on local context. For example, some districts will want an explicit focus on representation across cultures, identities, experiences and questions around this focus can be asked when assessing current materials or selecting new materials. It is also critically important to honor teacher expertise (around content and their students) and balance their autonomy with HQIM.

For example, educators in one county in Duval, Florida recognized that incorporating local history into the curriculum for their African American studies would not only help students better understand the historical significance of their local community, but that it would pave the way for increased student engagement and more positive learning outcomes.

The issue was finding relevant, Florida-focused materials, that weren’t biased or promoting a specific point of view, and then organizing them to align with the existing course and curriculum. The district reached out to a reputable K-12 content creator, XanEdu, to provide supplemental materials that would challenge students, fulfill the state’s requirements, and use the course’s existing units of study. Together they created a personalized learning tool: a collection of primary and secondary sources with a Florida-specific, local focus, aligned directly with the existing units.

Find additional information on culturally responsive supplemental materials in these resources:

What are key outcomes of this overarching process for selecting HQIM?

As more and more educators embrace the research on the importance of strong curricular materials, it is also important to recognize that HQIM is complex and requires skill and understanding at the district, school, and teacher level to implement well.

Professional learning should focus on the idea that teachers and leaders need professional learning experiences that are grounded in materials they will be using with students and structured around repeated cycles of inquiry.

According to Practice What You Teach, a 2017 report from the Aspen Institute, “Teachers deserve both materials and professional learning experiences that address the decisions they are making with their students in the context of the actual materials they are using. Providing teachers with generic strategies divorced from their day-to-day reality makes it less likely teachers will apply what they learn to improve practice or student outcomes.”

What does this look like in practice?

Faculty meetings and/or other school-level designated times are leveraged for building teacher knowledge and capacity with implementing standards-aligned instruction aligned to the district’s vision.

What are key outcomes of prioritizing professional learning?

While informed by the knowledge and skills teachers gain through professional learning, providing teachers with opportunities for collaborative internalization, planning, and practice supports the day-to-day implementation of HQIM. We know that adults learn best when they are engaged in a collegial process that draws on and values their experience as a resource in the learning process. An approach that focuses on the process of engaging with lesson content and materials before engaging in planning for lesson delivery provides teachers an opportunity to practice honing instructional skills in a low-stakes environment and receive feedback that will improve instructional delivery.

What does this look like in practice?

What are key outcomes of collaboration, internalization, and practice?

The good news is that we are seeing robust examples of districts successfully integrating HQIM through aligned support that builds off a shared vision of what strong instructional practices and materials look like and takes into consideration teacher and leader capacity and investment, professional learning, and opportunities for lesson internalization, planning, and practice.

For example, the Roosevelt Union Free School District (RUFSD) in New York worked with Education Elements to conduct a comprehensive review of its instructional materials after Roosevelt school teachers and leaders recognized that cultural relevancy was missing from much of the standard curriculum. With nearly the entire district consisting of students of color, it was important that materials not only be aligned with the state standards but also reflect the community’s culture.

“I knew the new Roosevelt model would have to include exposing our students to rigorous content, but the seasonal adoption of new texts was not going to be enough,” explained RUFSD Superintendent Dr. Deborah L. Wortham. With this urgent focus on equitable instruction, Education Elements engaged school and teacher leaders through a guided review of existing instructional materials to identify the most important components of HQIM for RUFSD. We also facilitated focus groups where teachers, leaders, families, and students were able to share their perspectives on equitable instruction.

In suburban New Hampshire, the Rochester School District (RSD) worked with Education Elements to intentionally build professional learning for teachers and leaders as the district rolled out a new core reading curriculum, while maintaining a deep commitment to Personalized Learning (PL). The team met with the publisher of the new materials and began designing personalized learning strategies that teachers could use with the curriculum. Each school at RSD had PL leaders who were trained by Education Elements and who, in turn, trained teachers at their schools during weekly early release sessions. There were also half- and full-day PD sessions at the district, with recorded sessions available for asynchronous teacher learning.

RSD strengthened its personalized learning practice while achieving a consistent curriculum for K-5 schools, which led to the number of students at or above national benchmark increasing across four grade-levels. (This is especially impressive in light of the disruptions to schooling during the COVID pandemic.) “Never have I seen kids reading like they are at this time in the year.” said Heidi Zollman, Curriculum, Instruction and Assessment Coach at RSD. (Read more case studies here.)

If you are interested in learning more about any of these steps, or need support taking the next step for your community or district, reach out; we may be able to help.